We remember the name Rosa Parks, who, in a silent but powerful movement of silent protest, sat in the whites-only part of a Montgomery bus. Yet, we forget about Claudette Colvin, who did it first — she refused to give her seat to a white woman on a crowded bus just months before Parks did the same.

We remember the name Martin Luther King Jr., the man who sparked a social justice movement and fought for African Americans to be equal to their white counterparts. Yet, we forget about those also instrumental in aiding him, like Bayard Rustin, James Lawson or Ralph Abernathy — all of whom played key roles in getting King to the places where he needed to dismantle Jim Crow laws. We know the names that get replayed to us every February, compressed into 28 days of quick poster, 28 fast videos and 28 swift days of conversation. For 672 hours or 40,320 minutes — 28 days — we remember to remember about Black history.As February slowly approaches, we just recall how much we are taught. As Feb. 1 nears, books litter the shelves about diversity, cartoonish posters plaster the walls and quotes are written on walls filled with inspiration.

As classrooms are filled, we learn only the bits and pieces of the entire history, a Black history. One that moves beyond textbook names of what Black power is, the curriculum leaves out the stories of those who succeeded in being the first beyond the Civil Rights Movement or the abolition of slavery.

It is a pause for a split second that works to amplify a story for just a few short weeks, then as March 1 hits, it fades. The posters might stay up, books may be kept on shelves, but the quotes are erased. The conversations stop. The doors begin to close and Black History Month is over before any of us even knew.

Just as quickly as we are uplifted, it is then pulled away. As the optional becomes an option again — it is hung back up on the shelf as the year moves on because the month ended.

With the closing of those short few days comes the close of the spotlight of Black history. With the closing of the month, we move back into American history, a history that more often than not limits out the voices, stories, and experiences of Black Americans.

With such limited time, there is much missed. We forget that ‘American history’ is Black history. Not just for the month of February, not only stories of resilience or oppression, but also stories of success beyond those involving rights and slavery. Stories that move to build on the successes Black Americans have. True remembrance means educating about stories of power, creativity and inspiration.

It doesn’t mean we don’t tell these stories; of course we do. They are part of our country’s history, but we also tell the ones of those who aided in building the country beyond. Limitation is what separates us from the narration that these stories are not American.

This moves beyond just how we shape our curriculum within schools, but also how we as adults access and understand the social contexts of the world around us. With the growing access to the internet and freedom to not just educate myself, but also others. We have to learn to learn about the overlooked.

Let me give you a list of some simple inventions: automatic elevator doors, three-light traffic signal, telegraph system and peanut butter. All were invented and patented by Black inventors. Yet, many of us would even be taught their names.

Black history did not begin when the first slave was released from slavery. It did not begin when the first march took place for equality. Our history began when we breathed out the words Black Lives Matter.

History is made in every moment of each day that a Black individual strives to make an achievement, a change, create stories, tell their experiences or strive for success. It is the building blocks of this nation that work endlessly to erase and limit us. The limitations of Black History Month are not an excuse for our history to not be shared.

These 28 days are a silent wounding message: we are not essential. Our struggles, successes, wins and failures are optional. For 672 hours, we teach our youth and each other that we have to fight to win. That to be Black, and win, you have to be denied who you are because history has no space for us. It is a subjugated, pre-selective remembrance that sugarcoats the idea that we as the people have one story.

In order to educate, we need to stop this calendar assimilation to look at the past through a small window view. Committing to telling Black history is a consistent measure to care, though an alive, breathing, ongoing narration of history. Until we can take these 40,320 minutes, we fail both our past and our present. Stop treating them like an elective course and teach them as an essential part of American history.

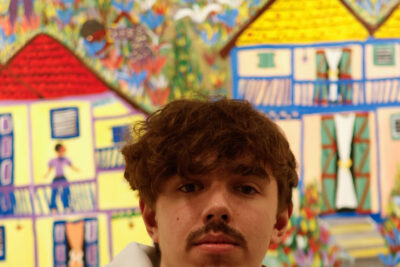

Kennedy Stewart is a senior Interdisciplinary Major, past BSU president and a current early education educator.