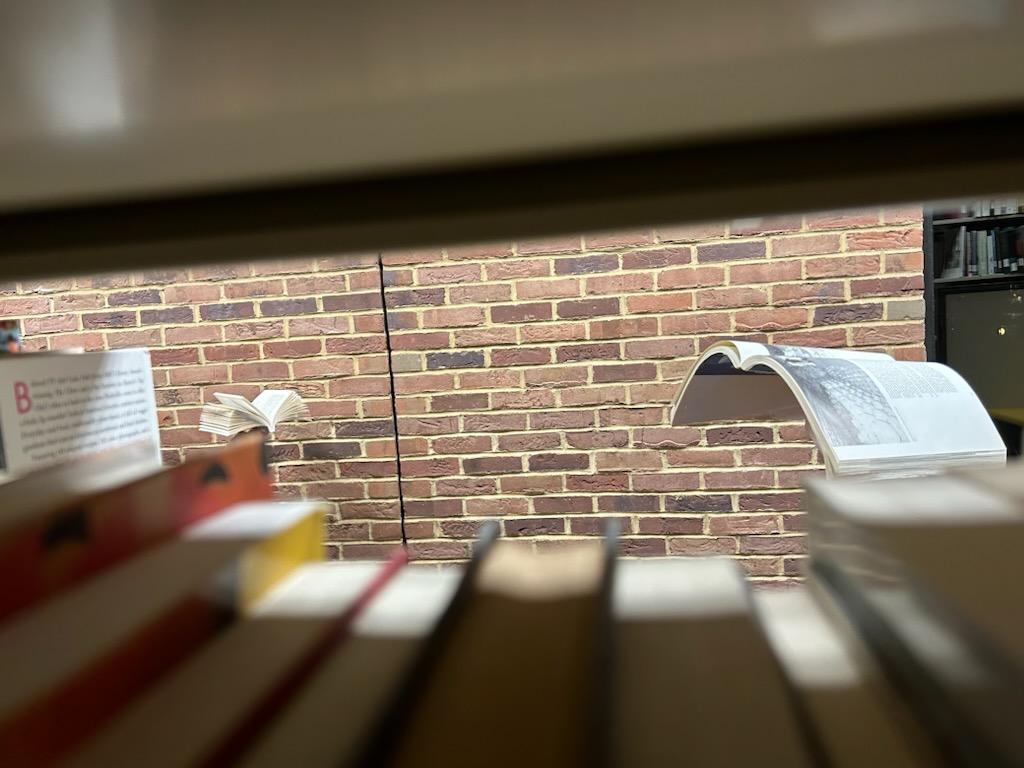

When the last light in the Good Library is extinguished and the doors are locked, the books push their covers against one another. Slowly but surely, they wiggle their way off the shelves, spread their covers and fly, with glorious inhibition. Nary a sound they make, save for the pleasant rustle of their pages.

Fly, little books. Fly and be free.The rolling chairs spin and perambulate the carpeted floors. Without human intervention, they’re restricted to the floor they’re found on (rolling chairs aren’t the best at taking the stairs). Which is better: to be a hard-working, blue-collar chair that serves the public? Or to be a specialized, luxurious upstairs chair, confined to the use of a single, loyal patron? It’s a question that has torn a great rift between the upstairs and downstairs chairs for generations.

I asked Breidlid’s “A Concise History of South Sudan: New and Revised Edition” for some history on the conflict from a book’s outside perspective. I became thoroughly versed in South Sudanese history throughout the interview, but after several hours was finally able to secure some detail on the closer-to-home civil dispute of the chairs.

“The three week peace talks ended in a deadlock since the parties could not agree on any of the important issues brought to the negotiation table,” (311) it said.

Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin” was a bit more blunt: “They’re foolish, impulsive, they argue and quarrel,” it said of the chairs, “but never a moment consider what fighting may lead to,” (81).

The chairs are no longer on speaking terms. Not that they were ever on speaking terms; chairs can’t talk.

Ah, to see the Good Library after hours. Stow yourself away in the library overnight? Not so fast. They sense you. They feel your presence. They freeze. They’re patient.

Books, after all, are smart. They hold, as a collective, far more knowledge than any human brain. Some, dating back to the 1700s, have far outlived any human being. When most people walk by, the books freeze; they can’t let us in on their secret. Correction: they can’t let YOU in on their secret. I’ve gained their trust.

As a Pokemon Go enthusiast, I walk around the Goshen campus every night from midnight until 6:00 or 7:00 a.m. playing the game; I never sleep. For the first few months of my uncommon behavior, the books and chairs remained frozen; they couldn’t risk me crossing past the library at the wrong time.

I knew their secret. How was it that I could take a book off the shelf that hadn’t been opened for years and be able to open it without difficulty? Don’t they get sore, or tense? If I was pressed together with hundreds of other humans, packed so close that I was unable to move, I’m sure I’d at least get arthritis. My theory was corroborated by my own observations; pages were uncommonly brittle in my months of night time wandering, and the infrequently used books were tearing at an unprecedented rate when opened.

I wanted to leave the books to their peace; I really did. When I discovered the pain inflicted upon them by my presence, I knew something had to give. I couldn’t give up my Pokemon Go nights. But they needed to fly free.

I wracked my brain. What would books find most comforting?

The voices of their parents. I went over to the Goshen Printmaking Guild and recorded the sounds of the old printing presses at work. I placed speakers throughout the library one night and played the recordings.

I peeked in through the windows, and the books, to my astonishment, fluttered down from the shelves. The sound of their creator disrupted their solemn defiance. They were stiff at first, but I could see them stretching and bending with increasing ease.

A tear trickled down my cheek. It was like watching hermit crabs arise from the sand during the night. Nature had returned to order.

“Fly, little books!” I cried. “Fly, and be free!”