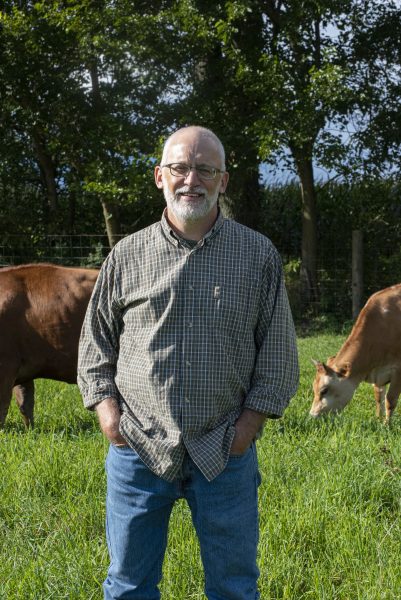

While many professors may choose to relax in their free time, Ryan Sensenig, professor of biological and environmental science, runs a mini agricultural operation selling grass-fed beef.

Sensenig and his wife have three to four cows on their farm at all times. These cows are eventually butchered, and the meat is sold to friends and other Goshen faculty members.Being grass-fed, specifically prairie-fed, it is much healthier than other kinds of beef and usually sells out quickly.

However, Sensenig is clear that the animals’ primary purpose is ecological research.

“The animals are there for the grass, not the other way around, so I use them to manage my prairie,” Sensenig said. “I do breed the animals and eventually butcher them and sell the meat. The bigger question, though, is what’s happening to the prairie.”

Sensenig’s research focuses on how grazing and fire disturbances influence soil carbon sequestration in prairie and grassland ecosystems. His farm has 12 acres of tallgrass prairie and four acres of cool-season and native grass. There are also research plots at Merry Lea and Mpala Research Center in Kenya.

Crucially and somewhat counter-intuitively, his research has indicated that grazing increases soil carbon sequestration, a vital part of addressing climate change.

“If we just had prairies without grazers, we would sequester a half-percent less organic matter,” said Sensenig. “Some scientists have suggested that if we increase our soil organic matter by just a half a percent in our managed environments, we’d more than offset all of the climate gasses that we produce.”

As an ecologist, Sensenig has mixed feelings about eating meat and believes it is essential to know what ecologically goes into making it. In his case, he believes that his “cows more than compensate for their carbon contribution… without the cows, we would sequester less carbon.”

Contrast his agricultural setup with a massive beef operation, and different conclusions will be reached about the ethics of meat consumption.

“It’s only the mass-produced feedlot corn systems where we’re producing tons of methane where I think the carbon is a really high cost,” Sensenig noted.

Selling the grass-fed beef is one example of Sensenig’s identity as an ecologist being interwoven with his entire lifestyle. He and his family live on a meticulously designed farm to eventually reach net-zero emissions. Solar panels produce energy for the home and power an electric car, and the house was crafted to minimize its energy requirements.

As Sensenig explained: “It’s also experimentation with how to live on the land. Sometimes we think of research as very narrowly defined processes that we collect data for, but this is also a research project for my family and I and how to live on the land in a way that feels healthy.”