It was around this time last year that I was wrapping a present for my mother.

I got her a book for Christmas: “A Parent’s Guide to Understanding Your Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, or Questioning Son or Daughter.”I read the book, and it was actually pretty awful. It did the job, though. I didn’t want to say it. The experience made me vulnerable enough that I could not muster the courage to utter the words: “I’m Queer.”

The words I had chosen to voice were planned out in the four months prior. Meticulous planning–down to every word.

“I hope you can love and accept me for who I am. I recognize that you might not support this lifestyle, and I applaud you for your steadfast conviction. I hope we can still coexist.” With these words I shared my gift and, in the process, validated any damaging ways of receiving it. At the time, I viewed an oppressive stance as a valid stance.

Coming out is a form of expressing one’s identity unlike anything else. I am a non-white man in higher education with a sustaining socioeconomic status, but I don’t really need anyone to receive this identity.

Coming out requires someone to receive a different part of me. I would not be able to come out without someone there to take and receive it. This aspect makes the whole experience challenging, awful and kind of beautiful.

As I wrapped this Christmas present, I folded in all my vulnerability and self-loathing, tucking it tightly under the creases. I needed my family to receive this gift that I had chosen to share with them.

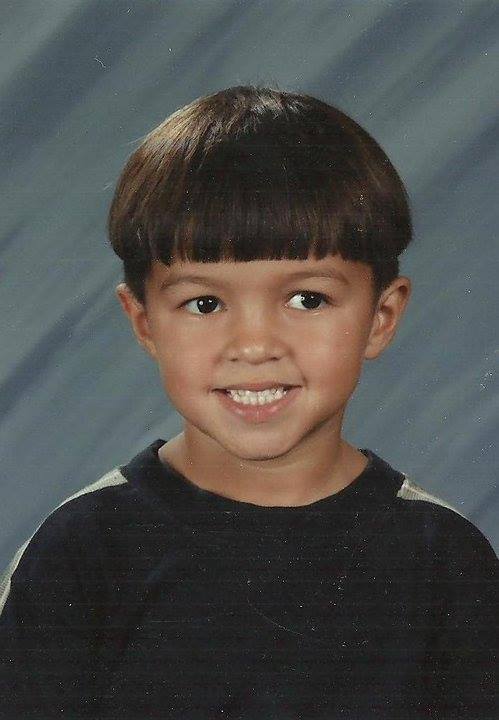

Christmas morning arrived, I came out to my immediate family, and I was left embodied. I, as a system of living and thinking and perceiving and feeling, was able to be fully embodied. I had known since I was about 6 years old, and for the first time since then, I was able to be fully alive.

Though I am living and thriving in this true embodiment, I reflect on the experience in regret.

I recall those words I had so meticulously planned: “I recognize that you might not support this lifestyle, and I applaud you for your steadfast conviction. I hope we can still coexist.” In this moment of liberation and self-expression, I viewed oppression as valid.

I have since grown-–to the point of coming out in this public forum. The journey is not yet done, though.

If my extended family stumbles upon these words, I may not be considered family anymore. I may not be celebrated at my birthday or be invited over this holiday season. I have relatives that express wholehearted disdain for gender and sexual minorities, and it is more than likely that I have given up my family today.

However, I’m glad this coming out to you is a bit different. I’m glad it comes at a time when I view my oppression as wholeheartedly and fundamentally invalid.

That is my Christmas present this year.