On Jan. 3, Goshen College men’s volleyball coach Lauren Ford left GC to take a job at Edward Waters University, a historically Black school in Jacksonville, Florida.

Ford’s departure was notable for many reasons, including her success with the team. Crucially, though, it marked the latest occurrence of a recent trend: women of color leaving GC.According to Justin Heinzekehr, GC’s director of institutional research and assessment, there were 16 women that were Black, Indigenous or people of color (BIPOC) employed by GC on Nov. 1, 2021.

On Nov. 1, 2022, 11 of those 16 were left.

Moreover, two of those 11 have since departed: Ford, and her fellow volleyball head coach on the women’s side, Kourtney Crawford.

In exclusive correspondence with The Record, Ford said that “it’s a problem” for the school. She mentioned that there are now quite a few “educated Black women that decided that Goshen wasn’t for them” in the past year.

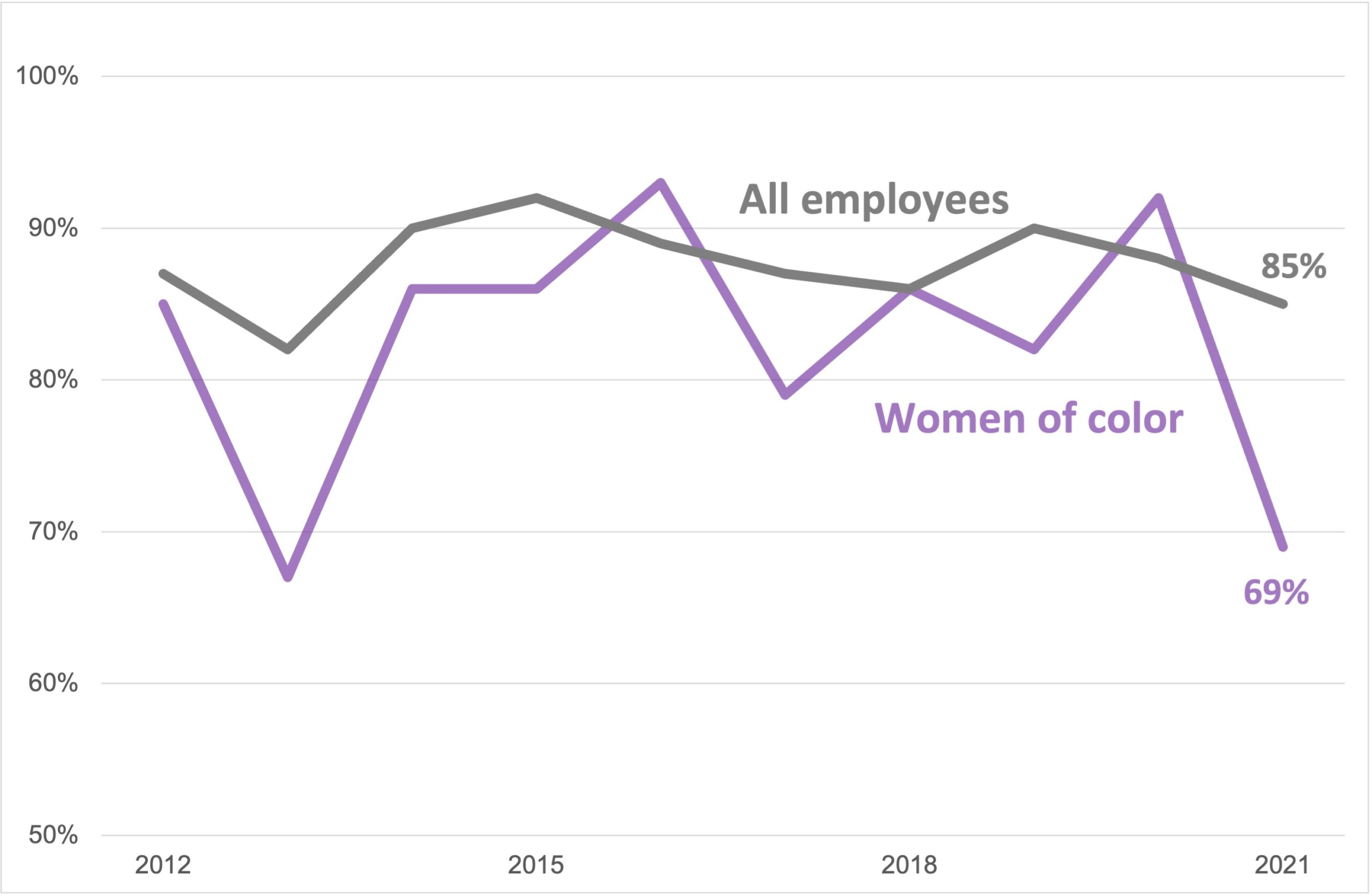

GC’s retention rate — the percentage of full-time employees that remain at the school over the span of a year — is a way to measure the rate at which employees leave the school. Looking at the past 10 years, the retention rate shows that Goshen has struggled for some time now with retention among BIPOC employees.

Based on an annual percentage from 2012 to 2022, running from Nov. 1 to Nov. 1 of the next year, an average of 82.0% of all employees of color returned to GC year-to-year.

In other words, every year, 18% of GC employees of color did not return to campus. That’s a retention rate of 6.5% lower than all other GC employees (88.5%).

It’s also worth noting that while just 49% of all students are white, 83% of GC’s employees are. That includes full-time teaching faculty, of which 92% are white.

Over the past ten years, men of color have typically had a much lower retention rate than women. However, this past year is a drastic exception to the rule.

Having and maintaining a diverse body is difficult to attain in higher education. The hiring market is competitive, and doctoral graduates already aren’t necessarily attracted to “a small Midwest liberal arts college with 699 students,” as Gilberto Pérez, dean of students put it.

“You have your Harvards, Berkeleys, U-Chicago’s,” Perez said, and “people of color haven’t always applied” to open positions at GC.

Other schools also may offer better opportunities to current employees, which makes retention difficult.

But regardless, in the words of Ford, “representation matters.”

“Students need to see people that look like them … to relate to,” she said. “Lack of diversity is an issue.” She added that while the lack of Black people at GC “wasn’t [the] main reason I left, it didn’t help.

So Pérez says that GC focuses on “creative hiring” processes — if full-time jobs aren’t available, hiring part-time positions that can “mentor” students — as well as being more intentional about “putting people of color in front of students,” through programming such as the Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebrations.

Yet these hiring processes can lead to wildly varying representation and diversity in different areas of the school. Ford described that although she felt more welcomed once she joined the student life team, “there are niches [throughout GC] that aren’t welcoming.”

Sophomore softball player Kamille Badibanga expressed a similar sentiment that GC may not be as welcoming and inclusive as it bills itself.

“[GC’s recruitment] really tried to portray themselves as a really inclusive campus,” she said, “and once you get here, it’s not what they made it out to be.”

“After Dr. LaKendra left,” she added, “they were not quick to try and find a replacement.”

Dr. LaKendra Hardware, director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at GC, left abruptly at the start of this academic year. Pérez and others stepped up to fill her spot on the DEI Committee, but Hardware’s departure left a void on campus, especially in regards to supporting Black students.

Marlene Penner, director of human resources, agreed with Pérez that it would be difficult to find someone to fill Dr. Hardware’s shoes.

“We want to hire people of color,” Penner said, “but we’re not the only institution who wants to do that.”

Yet some students feel like that needs to be made clear.

“I just think if they gave a statement about [the difficulties with] hiring, people would understand much better,” Badibanga said. “You don’t have to start big, but you can start small, with something like … seminars.”

Some changes are already underway, though.

“There are people there that are doing good work when it comes to bringing diversity to Goshen,” said Ford, naming Cyneatha Millsaps and Lawrence Giden.

Pérez agreed, saying that more and more, he sees students “engaging each other in inclusive events” such as last semester’s drag show.

Pérez called the drag show “incredible,” and mentioned how people of all different backgrounds and races were there. “The students that gathered there — if they would have the same energy for supporting other student groups? Holy cow.”

Staff are also working to increase a sense of community within the athletic department. For two years now, athletic director Erica Albertin has sat on the president’s cabinet and worked as part of the DEI committee, including athletics in these conversations.

Pérez said that he is “trying to bridge DEI and athletics [through] the intentional work of opening spaces,” mentioning that over the past year, DEI and the Black Student Union have worked on outreach specifically to Black student-athletes.

But students and staff require different support, and first-year volleyball player Kia Knox-Dawkins sees “more support going to student-athletes than staff [of color]” within the athletic department.

Badibanga said that communication and transparency is the first step to improvement. “If you want your Black athletes to feel like they have your support,” she said, “especially after losing two Black women head coaches, then I think you should state that.”

And that doesn’t just extend to athletes. With Goshen losing so many women of color across the board, Badibanga and others believe that publicly acknowledging the issue would be a powerful statement and would help provide, in Pérez’s words, “an inclusive and healthy environment for students.”

And to further that environment, staffing is crucial too. As Penner says, “we definitely need to create a culture that makes people want to stay.”

As for whether or not GC has a culture that attracts and keeps talent, Penner said, “To a point. But we definitely need to broaden it.”