Many have heard of the Miami tribe, an indigenous group that originally lived in what is now Northern Indiana. But “Miami” is the name they were given by the Europeans. The name they use for themselves is “Myaamia.”

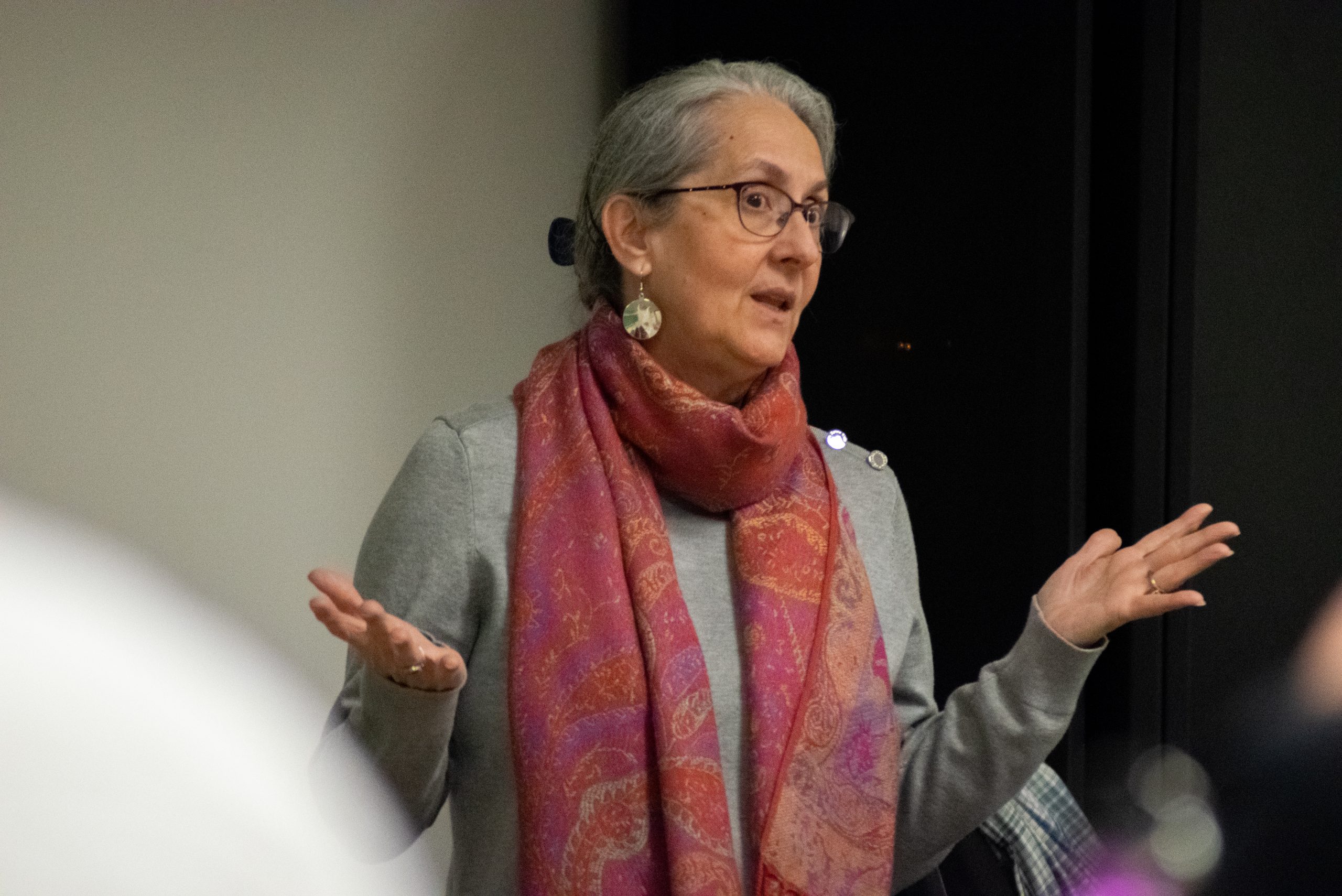

“Every story has more than one side,” said Diana Hunter, a citizen of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma who spoke at Goshen College on Tuesday evening. “You’ve heard the American story all of your lives, but hopefully you [hear] a little of our story today.”Hunter serves as a historic preservation officer for her tribe and was invited to speak at GC as part of the Sustainability Living Series hosted by the EcoPax club. Each week, the club partners with the city of Goshen’s environmental resilience department to host speakers on various subjects relating to sustainability. Past topics have included recycling, landfills and functional landscaping.

In her talk on Tuesday, Hunter shared how her people used to live sustainability on the land before the arrival of Europeans, and how they are working to make their community sustainable today.

Hunter began her talk with the origin story of her people.

“At first the Myaamia came out of the water,” she said. “Now that’s the first line of our oldest story.”

They emerged where the Saint Joseph River meets Lake Michigan, a place they call Saakiiweeyonki. “We learned to live there, to make our home there,” Hunter said.

As time passed, the group divided and spread throughout the Wabash River watershed and down to Fort Wayne, where they controlled the portage between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi watershed.

Hunter said that before the arrival of Europeans, the Myaamia led a sustainable lifestyle — because they had to.

They lived in small villages and split or moved when resources in one area started to become depleted. They planted their cornfields in floodplains near rivers so that the soil could be replenished in the annual floods. And when they hunted animals and gathered plants, they made sure to do so in a way that “meant there would be more … to gather later.”

The Myaamia had to care for the wellbeing of the environment because they depended on it to provide for their needs, year after year.

The Myaamia’s first contact with Europeans came during the Beaver Wars in the 1600s.

Over the next two decades, Europeans moved into the Myaamionki, the land of the Myaamia, gaining territory one treaty at a time.

Using a map, Hunter showed how her people’s land shrunk every few years until in 1838, they were left on only one small square of land: the Great Miami Reserve in what is now Kokomo, Indiana.

In 1840, the Myaamia signed away their last land in Indiana in exchange for new land in the West, and in 1846, they were removed by the U.S. Army and transported by riverboat to the Miami Reservation at Sugar Creek in what is now Kansas.

Despite the unfamiliar environment and lack of food and resources when they arrived, the Myaamia settled in and began to build their lives in Kansas. Then the Europeans arrived — again. And again, they wanted the land.

Today, the 6,000 members of the Miami Tribe are scattered between Indiana, Kansas, Oklahoma and other parts of the United States.

The Miami Tribe of Oklahoma is a federally recognized sovereign nation, headquartered in Miami, Oklahoma. They are currently undergoing a cultural revitalization.

Hunter was excited to share that last fall, the tribe bought a 45-acre piece of land near Fort Wayne.

The land is forested and with lots of walnut and persimmon trees, Hunter said. It will be used to host gatherings, grow traditional crops and hold summer camps for children.

Hunter concluded with the idea that “we are not a people of the past, we are a living people with a past.”