If you go to the Goshen College webpage for the philosophy minor and click on the “faculty & staff” associated with it, the website displays: “Sorry, unable to find any faculty with the specified category/tag.” The GC course catalog lists five classes in the department, but none were offered this year or last year.

According to David Housman, the faculty chair this year, the Bible and religion faculty proposed dropping the minor, which was discussed at a faculty meeting on Oct. 19. The discussion was ultimately tabled until the next meeting on Nov. 16. David Housman, faculty chair for this year, described what happened in the faculty meeting on Oct. 19. Isabel Massud for The Record

David Housman, faculty chair for this year, described what happened in the faculty meeting on Oct. 19. Isabel Massud for The Record

Housman described the “sadness surrounding” the future of philosophy at GC. “Just feeling like we’re losing something by doing this … I think faculty needed to think about that some more.”

Luke Kreider, assistant professor of religion and sustainability, said that although the philosophy minor is up for debate, courses related to ethics will continue to be offered whether or not the minor stays. Although they might not fall under the traditional “PHIL” prefix, Kreider will be teaching five courses relating to ethics in the upcoming three semesters, including Living Ethically in the fall of next year and Ecological Ethics and Environmental Movements in the spring of 2025. No course offerings are slated to be canceled.

Kendra Yoder, the chair of the religion, justice and society department, which includes philosophy, talked about the conversations happening in the department.

“We are doing some major work to look critically at all of our programs and look at what we are actually offering in terms of the courses we have faculty expertise in,” Yoder said.

Whether faculty resources exist on campus to provide the minor is up for debate.

Breanna Nickel, assistant professor of Bible and religion, said that the department is stretched too thin to offer it: “What we’re not able to do without a little bit more resources and infrastructure is have a degree program or have a designated professor that can keep those running.”

Ann Vendrely, vice president for academic affairs and academic dean, said, “More recently, we haven’t had the faculty expertise. We haven’t had the student interest in taking those kinds of courses.”

President Rebecca Stoltzfus sees things a little differently.

“I think we can teach a philosophy minor” right now, Stoltzfus said. “I think we have the faculty to teach that. There’s no doubt in my mind.”

Keith Graber Miller, a retired professor of Bible, religion and philosophy who taught for three and a half decades, spoke about the struggles he saw over his time at GC. “During almost the entire time that I was there,” Graber Miller said, “we struggled with having someone who had enough time in their portfolio to be able to offer philosophy classes or who had specific training to do philosophy.”

“We’d say, ‘Look, we need more time, we need more people,’” Graber Miller continued. “We’d sort of grab it wherever we could to get a couple of other philosophy courses that we would try to be offering along the way, but that fell away as our department got sliced and sliced and sliced.”

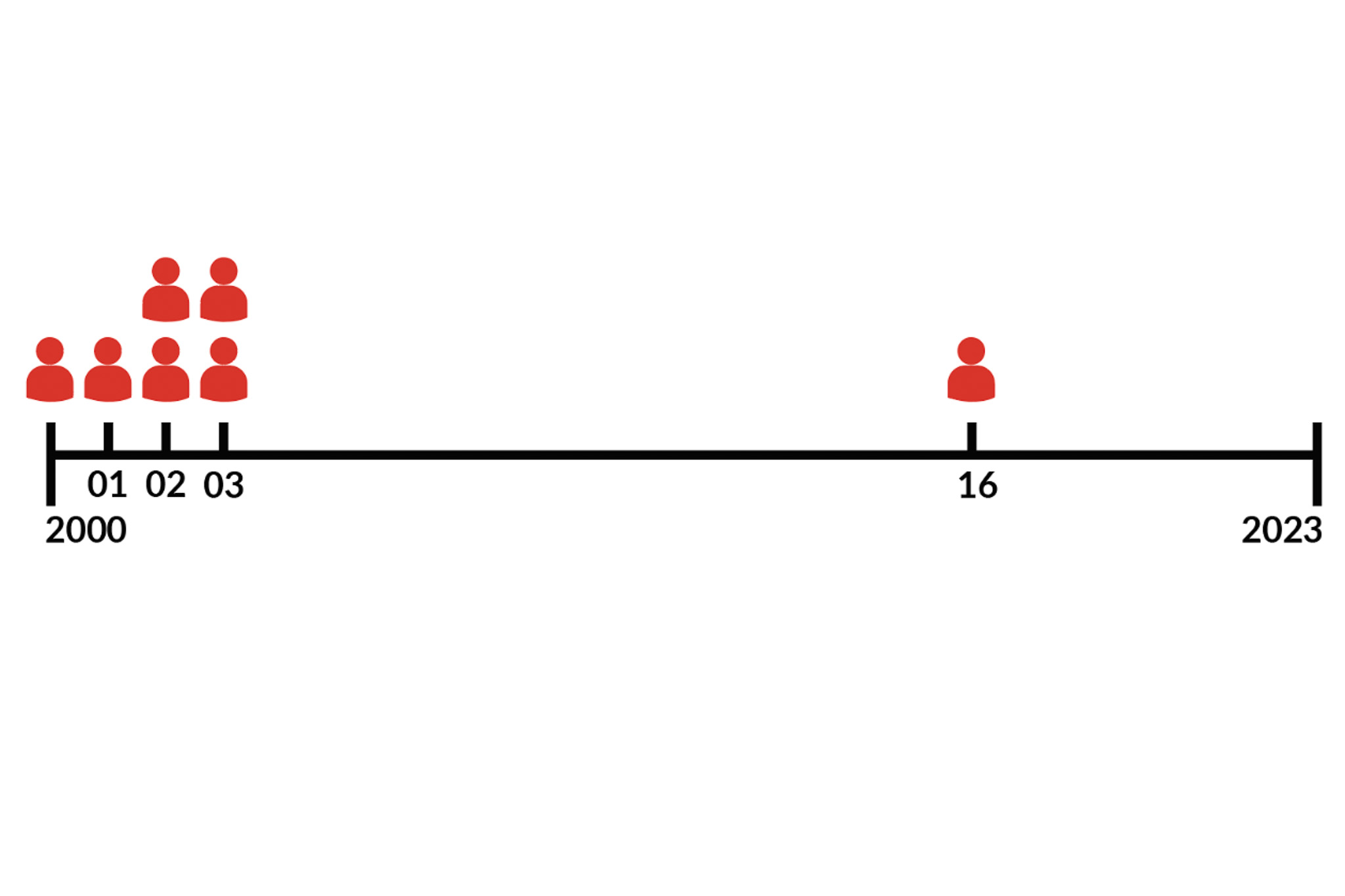

According to GC course catalogs, a minor in philosophy was first offered in the fall of 1999. In the 24 graduations since, only seven GC students have left with the minor, but the reason is unclear.

Vendrely said, “We certainly see nationwide these kinds of trends where students are not as interested in philosophy and the humanities. Maybe we could be the one that bucks those trends, but it’s a challenge.”

Stoltzfus agreed, saying, “When you look around the landscape of higher education right now, larger universities or places that are more invested in philosophy departments are having a really hard time in enrollment … it’s not a promising market.”

Despite this, there’s a strong desire from some faculty members to maintain the philosophy minor.

Nickel said, “From the point of view of recruitment … I do get a fairly significant amount of interest in both philosophy and in religion.” She said that students don’t always come to campus intending to study philosophy, “but then [they] take a class in it and find that it is actually incredibly impactful and meaningful and causes them to make a shift in terms of where they’re thinking.”

When asked if she would like to see a dedicated professor of philosophy, Nickel responded, “Yes, no question. Like I say, it’s a vital discipline.”

Yoder said that losing the philosophy minor would be “a huge loss. To me, it speaks to a much bigger conversation we’re having about what it means to be a liberal arts institution. … Are we only supporting the things that are driving [new student enrollment]? … If we’re only looking at student trends, then it’s the death of the liberal arts.”

Stoltzfus said that “I think the work of the faculty right now is to grapple with the reality of student interests. … Is a philosophy minor essential to being a liberal arts college? I would say no. If this thing were going to fall apart because of lack of a philosophy minor, it would’ve fallen apart 10 years ago, and it hasn’t.”

One part of the debate that received no attention in the faculty meeting is the Brembeck endowment for a chair in moral philosophy.

According to “Recollections of Sectarian Realist: A Mennonite Life in the Twentieth Century,” a book by former GC president J. Lawrence Burkholder, “in the late 1970s Howard and Myra Brembeck gave Goshen College a contribution for a chair in moral philosophy and also endowed the Carl Kreider chair in economics.”

An endowment funded in perpetuity, such as the endowments from the Brembecks, has an initial investment with a goal of generating income each year without dipping into the principal amount. Jerrell Ross Richer is the current Carl Kreider chair in economics; Vendrely said that she is “not aware” of the philosophy position ever being filled.

The Brembecks donated hundreds of thousands of dollars in the 1980s to establish a “professorship in moral philosophy,” but guidelines for the fund’s use were never finalized, according to internal documents provided to The Record by a GC employee, to whom The Record granted anonymity due to the college’s policy on confidentiality for donations.

According to Todd Yoder, vice president for institutional advancement, the endowment “was not restricted to solely fund a philosophy professor position.”

Stoltzfus said that endowments under “around $2-3 million” can’t fund an endowed chair or a single professorship. Endowments also usually provide alternative options if the original stipulations cannot be fulfilled.

Stoltzfus said that the money supports the religion, justice and society department. Logistically, though, the income from the endowment for a chair in moral philosophy, along with many other endowments, go to the operating budget of the college — in effect, supporting all operations on campus. In these cases, no single department sees an increase in departmental funds as a result of endowments.

“We’re fairly egalitarian in our departments,” Stoltzfus said. “This is not just about the Brembeck gift or the Bible and religion department in general. When people give to support departments, in this kind of way, it doesn’t mean that the Bible and religion faculty get paid more. … That’s the common way it’s done.”

Howard and Myra Brembeck both died over a decade ago, and their only daughter Caryl Chocola died in 2019. The Record reached out to their grandson Chris Chocola, who, as it happens, was a U.S. representative for Indiana’s second district (which includes GC) from 2003-07.

“I wouldn’t assume [my grandparents] would have intended for it to be for general operations,” Chocola said. Since it is not restricted, though, he said “I guess the college has the leeway to do what they want.”

Chocola serves on the board of another college, and said that he understands the dynamics of how colleges use gifts, but believes that “in a perfect world, [his grandparents would have] liked to see the money continue to be used for its original intent.”

Despite the lack of philosophy classes, there are several students on campus who expressed interest in more being offered.

Alex Koscher, a senior history major, said, “History has a pre-law track, which I’m doing, and so I wanted to add philosophy because I thought it would look good with my major.

“All of the classes were never listed” in the course offering list this year, Koscher said. “Otherwise, I probably would’ve taken at least one or two of them.”

Elijah Stoltzfus, a senior environmental science major, said he took a philosophy course at a community college before coming to GC and hoped to take more.

“I was even thinking about doing a philosophy minor at one point,” he said, “but I just heard that the program wasn’t really all that exciting. There weren’t really that many people involved with it, so it just didn’t seem like something I wanted to get into.”

Amy Drew, a junior psychology major, said, “I actually was looking into it — I think last semester — but I don’t think I found any that fit in with my schedule at the time. … If there were options and I could fit it into my schedule at some point, I would’ve taken one.”

When asked if GC should get rid of its philosophy minor, Drew said, “I don’t think so. I feel like philosophy should be offered in colleges just because it kind of gives people a better understanding of themselves and the world.”

The faculty will revisit dropping the minor on Nov. 16, and while the outcome is still unclear, Graber Miller’s thoughts are not.

“It’s ridiculous,” he said. “I don’t know how you can be a liberal arts college in the 21st century and not have philosophy.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated on Nov. 2 to give additional context that although the philosophy minor is up for debate, classes relating to ethics will continue to be offered regardless of the status of the minor. No classes are slated to be canceled.

With reporting by the authors and Daniel Eash-Scott