This month at the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, countries around the planet are being called to redouble their efforts to bring greenhouse gas emissions to zero by the middle of the century. Reaching that mark is critical for keeping global temperature rises below 1.5 degrees Celsius and avoiding increasingly severe environmental catastrophes.

Goshen College committed to the goal of zero emissions by 2050 in 2007, when the president at the time, James Brenneman, signed the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment. Is the college on track for reaching that goal?The Sustainable Tracking, Assessment and Rating System (STARS) evaluations carried out by the college every five years since 2011 provide some insight.

The reports separate greenhouse gas emissions for institutions of higher education into three categories. Scope one emissions are produced by the combustion of natural gas on campus (i.e. heating and cooling), while scope two emissions come from electricity purchased by the institution, and scope three emissions include everything else: air travel, commuting, and waste.

The most recent STARS report, completed in 2020, revealed that, in the year 2017-18, the college emitted 2,959 metric tons of carbon equivalent between scope one, two and three emissions. That is less than half the emissions reported for the year 2012-13, which came in at 6,581 metric tons and almost a third of the emissions reported for the baseline year 2007-8. Data on scope three emissions is not available for 2007-8, but an estimate based on numbers from the other two years puts the 2007-8 total over 8,000.

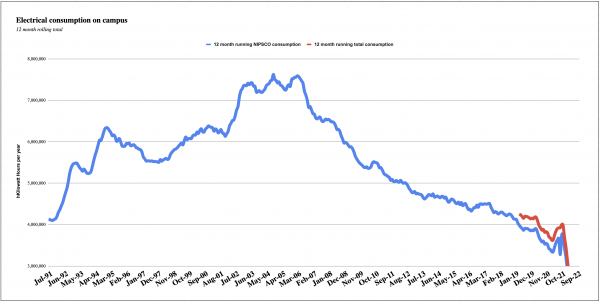

Goshen College’s electrical consumption over the past three decades.

Goshen College’s electrical consumption over the past three decades.

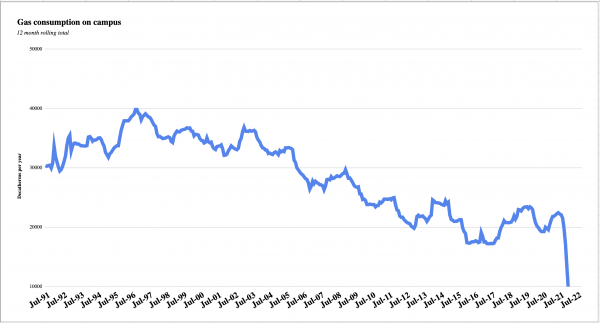

Goshen College’s natural gas consumption over the past three decades.

Goshen College’s natural gas consumption over the past three decades.

The decreases in the last decade have mostly come from changes in scope one and two emissions.

Steve Shantz, systems supervisor and EMS coordinator, has been working to improve the efficiency of many systems on campus since he arrived at Goshen College in 2006.

“If you look at the electric chart, the highest point is when I started,” Shantz said, pointing to the mountain-shaped curve representing the college’s consumption of electricity over the last 30 years.

Programming lights to turn off when not needed, replacing inefficient appliances and, most recently, changing almost all light bulbs on campus to LEDs have all helped to draw down the campus’ energy usage. Since electricity use peaked at over eight and a half million kilowatt hours for the year 2006, the number has declined steadily, and is now well under 4,000.

Besides using less electricity, Goshen College has begun producing some of its own renewable energy. In 2018, 923 solar panels were installed on the roof of the Recreational Fitness Center as part of a joint project with College Mennonite Church. And as of 2013, the college purchases all of its electricity through a renewable energy credit program, which means that it counts as “green” energy.

The use of natural gas has followed a similar trajectory. In this case, the changes are due in large part to the phasing out of steam heaters in favor of high efficiency boilers (still powered by natural gas). Getting rid of steam is a priority for Shantz who referred to it as “our least efficient heating source and a maintenance nightmare.”

But moving away from natural gas is more difficult. While geothermal may appear to be a good alternative for heating and cooling, these systems use a lot of electricity, which means they need to be paired with renewable energy sources in order to be carbon-free; otherwise they just raise the electric bill.

Natural gas is currently the most efficient heating technology available, Shantz said.

If GC does reach carbon neutrality, he predicted that “the last thing to go will be our natural gas boilers.”

While just as important, scope three emissions have been both harder to calculate and harder to reduce. So far, little has been done to address the main contributors in this area – commuting and air travel.

“International travel, including SST travel, is a major source of our carbon footprint,” said President Rebecca Stoltzfus.

Jan Shetler, director of international education, said balancing the college’s goal of carbon neutrality with the value placed on international experiences – including chances to see the effects of climate change on developing countries first-hand – is challenging.

This may be an area where carbon off-setting, as opposed to carbon reduction or generation, is the best option.

“We are working on plans for thinking about carbon off-setting by calculating the carbon we burn and then giving that money to an organization in the countries where we do SST …” Shetler said.

But she added, so far “we have not found a sustainable way to secure the financing to support these costs.”

Last month, Goshen College’s board of directors approved a new strategic plan which lays out the college’s priorities up to the year 2027. The plan includes goals specifically related to sustainability, including “institutionalizing leadership in environmental sustainability” by the end of 2022 and going off of steam energy by 2026.

In addition, the college hired a new vice president for operations, Ben Bontrager, this week who will work with the sustainability committee to develop a new sustainability master plan for the college.

“We need to do that work to answer [the] question of whether we are on track toward our goal to become carbon neutral by 2050,” Stoltzfus said, “and what additional measures would be needed to get us there.”

Solar panels on the RFC help GC produce clean energy.

Solar panels on the RFC help GC produce clean energy.

The next couple of decades will prove just how dedicated the college is to meeting that goal, as the last ton of carbon will be much harder to eliminate than the first.

“We’ve done most of the low-hanging fruit,” said Shantz. “The things that were easy to implement or had big savings, we’ve already done most of that.”

“Up until now,” Shantz said, “everything I do, I try to make it invisible.”

But that won’t be possible for much longer.

If carbon reduction is to continue, students and employees will need to accept some inconveniences, including indoor temperatures that fluctuate more with the seasons, less illumination at night and more restricted use of personal appliances including mini fridges.

Shantz asked: “What would people say if I turned off the fountain in Schrock Plaza?”