Born in 1943 into a family of African-American migrant farm workers living in cramped quarters two miles down the road from Lake Placid, Fl., Lee Roy Berry Jr. declares that, truth be told, his childhood home was anything but placid.

As a boy, Berry traveled from Florida to Ohio every summer with his parents and seven siblings, chasing the seasonal crops to his parents’ boss’ home state. Lee Roy Berry Sr. and Nettie Mae Hawthorn Berry helped maintain and harvest “any crop you can mention,” according to Berry. Starting at age 8, Berry joined his parents in the fields in the summer and on Saturdays, pulling radishes, skinning onions and weeding, even in the rain.“I was aware of the stigma that we, as migrant kids, had,” said Berry.

But in his life, this stigma was based more on socio-economic class than on race. “We dealt with white people,” Berry said, “but we never associated with white people when I was young. Whites were not our primary reference group. We had to relate to them, but not in an intimate way.”

In the migrant camp, Berry Sr. referred to his white boss on a first-name basis, but interactions with white people were confined to work settings.

Crime and conflict were common facts of life to young Berry. His brother’s friend Lindbergh was killed in a pistol duel. His mother caught his father cheating on her and beat Berry Sr.’s lover up while Berry Sr. made a run for it.

With an upbringing like this, Berry said, “You begin to suspect the wolf’s presence much more quickly.”

He saw what this life did to his mother. Berry saw how his father abused his mother and how she, in turn, abused him. Berry said that even as an adolescent he “wanted a life that was better.”

1958 was a recession year. Since there were not enough jobs on the farm to support the usual crowd, Berry Sr. took off for Green Pond, S.C. in search of work. He didn’t return until 11 years later. At age 14, Berry was partly responsible for his family. “I worked to provide for the family,” he said. “I was the little man around the house.”

Meanwhile, Berry’s father had an affair and seven children with a woman in Green Pond. “I think he wrote us off,” Berry said.

Berry would see his father only once more in his life (when his sister died in 1969), but he does not personally blame his father for his father’s faults. “My dad was a child of his time, a creature of his environment,” Berry said. “He was probably lucky that he even survived.”

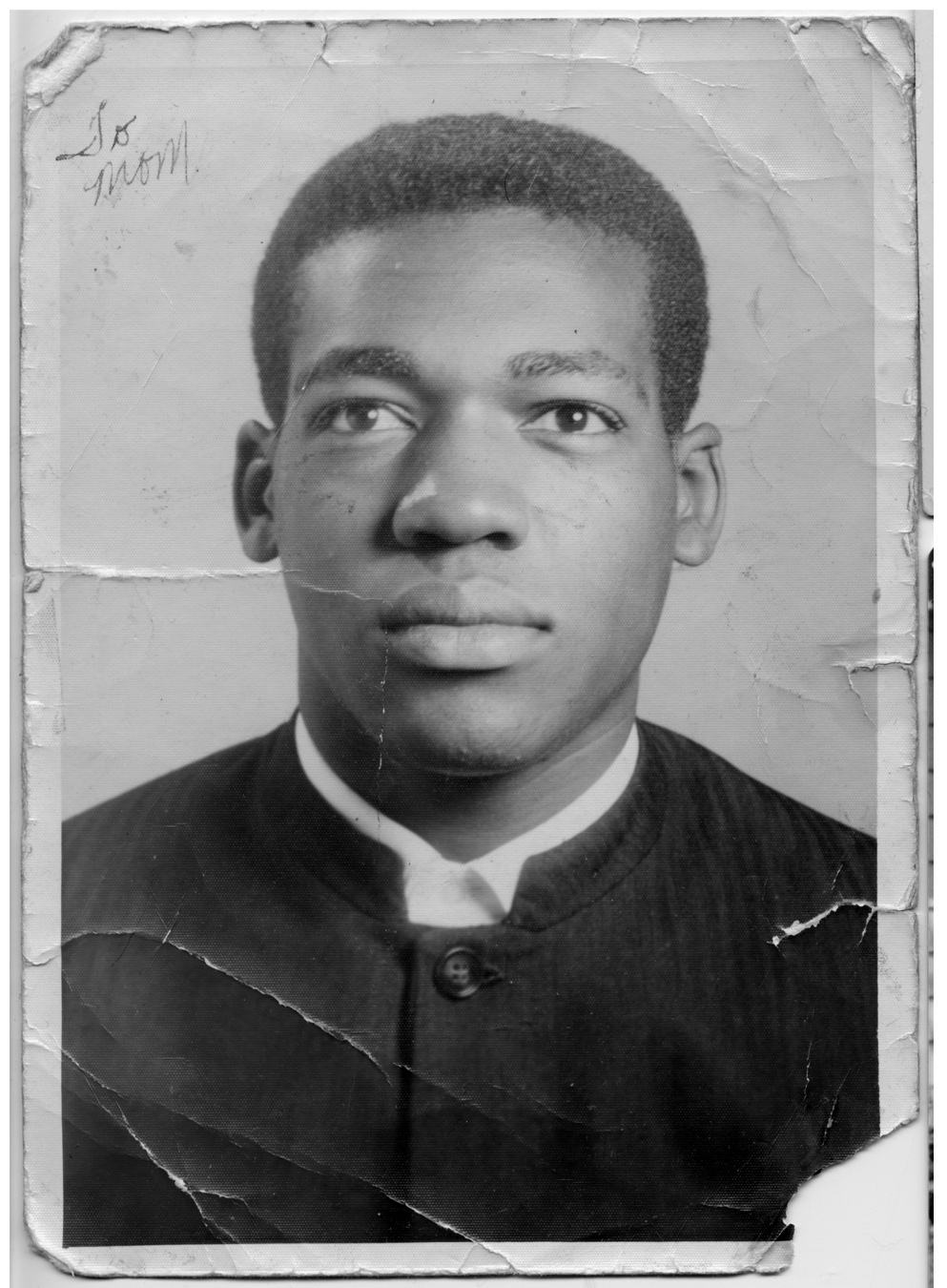

In 1961, Berry graduated from a segregated Sarasota, Fla. high school. The segregated school hadn’t offered him a very good education, but Berry had a keen desire to improve his position in the world. When it came time for his teachers to identify talented and potentially college-bound students, Berry’s name was brought up.

The news circulated quickly in New Town Gospel Chapel Mennonite Church. “When my preacher heard me talk about going to college, he almost fell off his bench,” Berry said.

This same pastor eventually came around to the notion of Berry going to college; however, he encouraged Berry to look into Eastern Mennonite College in Harrisonburg, Va.

Berry attended the college from 1962 to 1966 and received his bachelor’s degree in history there. “I was, in a sense, out of my element,” Berry said. But he gave it his all, nonetheless. His mother, he said, was “tickled” to have a son in college.

After Berry graduated, he went into voluntary service. He worked at a summer day camp in Cleveland run by a woman named Beth Hostetler.

After talking and visiting with Hostetler a few times, Berry said he “got hooked.” Raised in a white, Republican, middle-class Ohio family, Hostetler did not exactly share Berry’s upbringing. But “on an intellectual level, I liked talking to her,” Berry said.

The two got married in 1969. In the years that followed, Berry moved to Goshen, began teaching political science at Goshen College, continued to work on his Ph.D. at the University of Notre Dame and became a father to Joe, Malinda and Ann Berry. In 1984, Berry got his law degree from Indiana University and now works full time as an attorney in downtown Goshen.

Berry’s law career originated with an experience he had when he was a boy.

One day, his mother was washing clothes with a rub board behind their house in Lake Placid – the sun streaming down on the heap of clothes beside her – when a white man drove up to the house and introduced himself to Berry’s mother as a lawyer. The lawyer threatened to take their home away as Berry’s mother and father were behind on the mortgage.

Berry’s mother cried and cried while young Berry stood silently by. “I saw that the lawyer had power,” Berry said, “and I knew that I wanted to be one someday.”

The story has finally come full circle. Now that Berry himself is a lawyer, he urges his many blue-collar clients to take full advantage of every opportunity to better themselves. Recently, Berry prodded one African-American client into registering to vote.

Only education, Berry believes, can break an entrapped mindset. “If you cannot examine your culture’s strengths and weaknesses, then you’re gonna be bound by it,” he said. “And to be bound by it makes you less of a human being.”

Looking back on the boundaries he has broken in his own life, Berry considered the place of African-Americans in society today. “What I really can’t stand is to see African-Americans who have the opportunities but who throw them away with both hands,” he said.

“There’s a moral obligation, it seems to me, for African-Americans to take every opportunity. Not to do so verges on the criminal,” Berry said, a strong statement from a lawyer.

Today, Berry continues the work, he has been doing for nearly 40 years at Goshen College and at his law firm. The economy “has thrown a monkey wrench into my retirement plans,” he said, smiling.