I have heard Lee Roy Berry speak on justice and race before, so I am familiar with his deep voice, confident presence, and thoughtful words. I have heard his former political science students praise his teaching. I felt shivers anticipating my interview with him. But, I noticed that my nerves were twitching not just in respect, but also in fear of the “race issue.” I am passionate about anti-racism dialogue, but I’m afraid of my own privileged ignorance. I’m afraid to say something insensitive.

Nevertheless, Martin Luther King Jr. Day rolled around and I attended a spoken word coffee house on race. The room of silent, eager eyed on-lookers filled with the voices of students reading the words of Maya Angelou, Natasha Tretheway, Langston Hughes, King and others. But the last reading was an original piece. Tears rose in the throat of the author, Dominique, and wet the eyes of her audience as she shared a story in which her mother ached for her white peers to advocate for her minority experience after the results of the Trayvon Martin case were announced. It ended with these lines:“‘When will the white folks speak up?’ My mother asks me. ‘For how long,’ she says, ‘do we need to be speaking out against the hate that we experience on a daily basis before things will change?’ she says. ‘When will the white folks speak up?’

I have a skewed idea of what church family is, because this man that I see every Sunday, can spew to me his indoctrination–bloodied with bigotry–and not even notice the color of my skin. Because I am afraid of having a brown-skinned son who could be murdered and the very people who he will sit next to in a pew every Sunday morning can one day condemn him because of it. We are the light on the hill, oh people. So shine, already.”

This summons encouraged me to step past my fear of saying something wrong. As I drove to the Electric Brew to interview Lee Roy my heart pounded now to the beat of excitement rather than fear.

He arrived in overshoes and a casual sweater, not the bow tie and pressed suit of a workday; this was a holiday, and the conversation that followed was equally relaxed. Through his lifetime living in both the Jim Crow South and then the predominantly white city of Goshen, he both experienced and observed the evolution of racism.

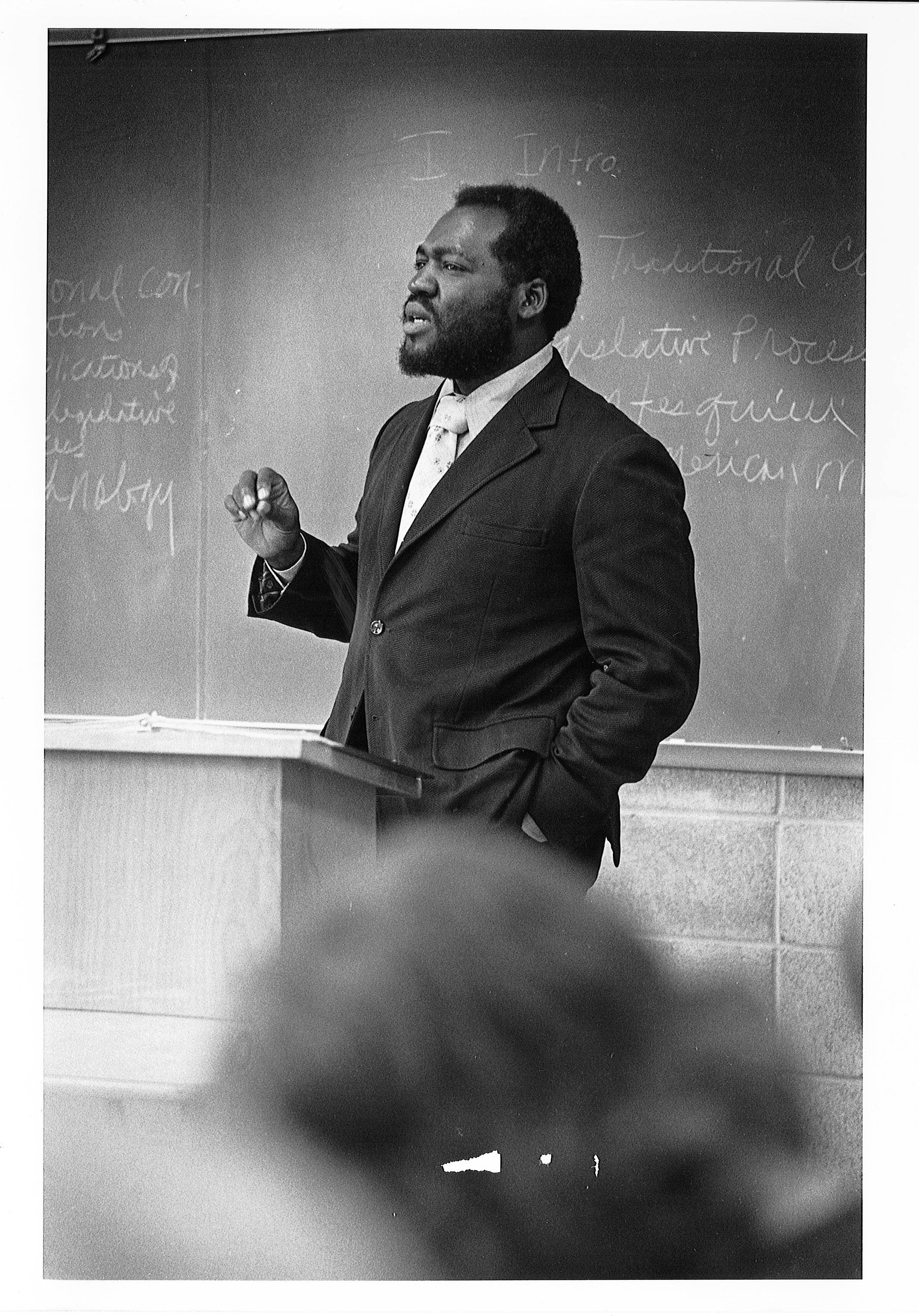

We talked little about his life as a lawyer, as a college professor of political science, and of being a husband and father in an interracial family. This meeting marked ten years since he gave this speech about differences between white and African American Mennonites. So, I asked his reflections on the intersections of race, politics and religion today.

“What race did in the United States and what it continues to do was deprive us of being genuinely human. If you mess with minds long enough then it becomes a way of life, it becomes culture. So, that’s our legacy.

I think the challenge is to try to resolve the race problem and that requires a huge change. And change is hard, very hard.”

I heard an echo of Dominique’s cry when he said this. So I read her piece to him. In response he said, “I would say to your friend here, this is something that we’re born into. She didn’t have the choice to be born. I didn’t have the choice to be born. So, I have to work in the context in which I exist. That is one of a society that is burdened by race and it’s legacy.”

He explained how this burden affects relationships in and outside the church. He said, “There’s a tension there. On both sides there’s a lack of comfort because whites think Well I’m going to say something insensitive, while blacks think I’m worried that I won’t portray my black identity.”

I nodded, remembering my own discomfort anticipating this interview.

“I mean, my wife and I, we married back in 1969 and we had people telling us we shouldn’t get married because we were different and because our children would be despised, but we got married. There weren’t as many people getting married then but the number of interracial marriages have increased since then.”

And yet, race continues to inhibit his family. Lee Roy leaned back to tell another story.

“After the Oklahoma city bombings, my nephews were traveling from Oklahoma to Florida for Christmas vacation and they were stopped in the state of Georgia for some reason or another by a police officer who saw their Oklahoma license plate. Was that race? I believe it was, because the police officer has a certain amount of discretion. Well, the members of my family got out alright, but this could happen most any time.”

So how do we live with this? What do we do? I was wondering. I did not have to ask. He went on, “I think the challenge to black Americans is to find ways to deal with these kinds of issues effectively without becoming violent or assuming the worst and yet, not invite them. I also think of the challenge to what Martin Luther King called “white people of good will” to recognize and admit that our whole foundation and the ethos of our culture, is rooted in white supremacy. To the extent that we get along okay is the extent to which we are overcoming it.

But it still remains like a cancer. You may have been able to stave it off, and prevent yourself from it, but it’s a continuing battle. That’s what it means to live in America, to live with race.”

However, many people do not seek to understand issues of race, Lee Roy said. And, as I can testify, some get too trapped in fear to discuss these issues.

“There’s nothing wrong with being comfortable,” he said.

“I mean you’ve got your routines, the people you associate with, that’s your world. To the extent that your world is not touched by things that are ‘racial’ then it’s alright.”

He went on to exemplify. “My late father in law was a Republican, he grew up in small town America. His parents were farmers; they were hard workers. He raised his daughters expecting they would all marry white, successful guys. That was his world and he had every right to expect that. So, it was a shock for one of them to come home with a black guy (Lee Roy) and say, “I like this guy and I like him so much that I think I want to marry him.” That was… wooooo… that’s an adjustment. In the course of time he comes to know me, he comes to know the children, he’s less apprehensive. That’s a cultural adjustment. That’s the way changes occur.”

“Through relationships?” I said.

“Well in part, relationships and if we are conscientious on both sides we can be fairly successful at it.”

“What does that require?” I said.

“I think it’s honesty and vulnerability. And toleration, we will need lots of it.”

These words were encouraging, but this legacy of race we had discussed still felt like an impassible barrier. So I asked, “How do you reconcile this sense of doomed fate along with hope in young people?”

“Because there’s an evanescence in human communities and things do change of their own accord.”

Lee Roy’s life is part of that change. We had time for one more story, so he told me about a summer job when he was 18. It was the summer of 1962. He said, “There was one time I was working a job. We were all black guys working and this white guy was our head. Our job was to clean the roads in the summer time. I was carrying out my responsibilities when a car drove by with a driver who was white woman whom I knew, so I waved at her. A few moments later the supervisor said ‘What are you waving at a white woman for?’ So he fired me. To teach me a lesson. I got another job. I saved my money. I went to college. And I waved at a lot more white women. And then one said ‘Okay’ when I said ‘Come, go with me.’ And so then, there we are.

I have a grandson now, this is his legacy. In a sense his future is shaped by this. And you, this is your legacy.”