Duane Stoltzfus, chair of the communication department, received an email on Feb. 7 with the subject line, “question from a journalist.”

It was from Malcolm Gladwell, renowned journalist and podcast host of “Revisionist History,” which Gladwell describes as “things overlooked and misunderstood.”He was planning a series of episodes about the Minnesota Starvation Experiments.

In the early 1940s, conscientious objectors were faced with a dilemma. By definition and principle, they could not morally justify going to war. But the war was precisely where their country was headed.

“By World War II,” Stoltzfus said, “We had the Quakers, Brethren and Mennonites getting together and talking with the government and figuring out a way to have civilian public service camps that would allow COs [conscientious objectors] to do work of national importance.”

Participation in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment became one option. Thirty-six single male volunteers were meticulously selected to live in the basement of the University of Minnesota football stadium from Nov. 19, 1944, to Dec. 20, 1945.

Those who participated were fed a set amount of calories for the first three months to reach their “ideal weight.” Six months later, the men were constantly monitored and allowed to consume only half of their normal caloric intake.

One of these men was Lester Glick, a Goshen College graduate and the founder of GC’s social work program.

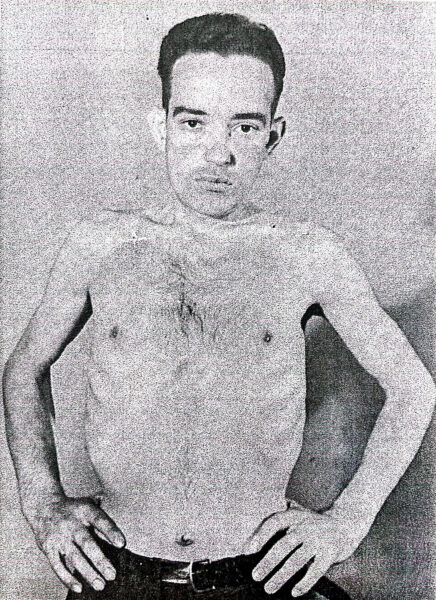

Lester Glick, pictured here post experiment. Contributed by the Mennonite Historical Library

Lester Glick, pictured here post experiment. Contributed by the Mennonite Historical Library

The experiment’s goal was to study the effects of prolonged, famine-like starvation on healthy men and the functionality of various rehabilitation strategies. This type of research was especially crucial post-World War II, with concentration camp survivors and refugees worldwide experiencing these conditions.

The study produced a seventy-page pamphlet distributed throughout war-torn countries, as well as a landmark two-volume, 1,385-page book entitled “The Biology of Human Starvation.”

It also had profound, shocking effects on its participants.

From Lester’s journal on July 8, 1945:

The drive for survival.

All body functions such as pulse rate, heart size, respiration rate are reduced to optimally utilize those limited calories which are available to sustain body functions. Cannibalism, death through starvation, grass salads and eating garbage are more than fleeting thoughts. We are told that we are starving so that thousands of starving people might be fed. Such thoughts are fleeting, and I’d give them up in a minute for a few slices of bread.

The devastation of hunger wasn’t just physical.

“In his hunger, he was becoming isolated; antisocial,” Gladwell said. “He started to dislike the company of his fellow guinea pigs.”

The effects of Glick’s hunger stayed with him for the rest of his life.

“He never got over being hungry,” Byron Glick, his son, said. “He was always hungry, even when he had all the food he wanted. Something had happened in his physiology that broke the connection between his stomach and his brain.”

While prolonged starvation traumatized Glick, he never expressed regret for his participation.

“The participants in this research went into it with their eyes open,” Stoltzfus said, “and with a kind of clarity about the research study and some of the risks. My sense from Lester Glick was that he remained a believer in what he had done and that he would have made the same decision again.”

This episode can be found on any podcast platform, entitled “The Mennonite National Anthem,” in Malcolm Gladwell’s “Revisionist History.”