Carina Zehr

Contributing writercarinaz@goshen.edu

“So…do you want a duck?” Steve Shantz of the systems department asks me during break one November afternoon. He is asking me if I would like to purchase a full-grown, free-range duck to have as my next meal. Because I live off-campus, supper eaten together as a whole house is a special occasion. Having duck for supper would be the ultimate culinary treat along with, for some of my housemates, a first time experience in processing (butchering and cleaning) their own meat.

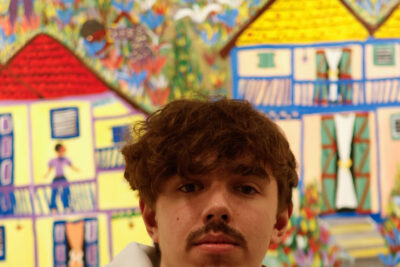

On a fateful Tuesday in January, Mr. Shantz knocked on our door with the duck in tow. I’ll spare the gory details, except that Quinn Brenneke, editor-in-chief of The Record, was the one to behead the duck as Karina Kreider, fearless EcoPax leader, and I held onto it.

Before deciding to buy this duck I thought through the ethical implications thoroughly (or so I thought).

1. It was raised well (good job, Steve).

2. Thanks for life was given.

3. Death was as quick as possible to minimize suffering.

4. As much of the bird was used in order to waste as little as possible.

However, after the duck died, a negative space was left inside of me that made me take a step back and look at what I had chosen to do. Did I do something wrong?

Upon hearing of the butchering incident, people generally had one of two responses: “How could you!?” and simply, laughter. When I said that I did not feel good, but was not able to explain why, they decided that I had probably named it. No, I did not give it a humanizing name or make it a pet possession. Why do living beings have to be humanized for us to care? Could not the duck matter as a duck?

And for those who asked me, “How could you!?” when they were still able to eat meat from the grocery store without a second thought, I have a story for them.

My high school years were spent in a small town in south-central Kansas. My mother was the unofficial social worker and Spanish translator for the growing Hispanic population that had moved in following the work that a new meat-packing plant provided.

She told me stories: the story of a man whose hand was chopped off by one of the machines and no further security measures were taken by management after the accident.

There is also the story of a six months pregnant Latina woman, whose undocumented status robbed her of the right to paid maternity leave, forcing her to work in those same dangerous conditions. She worked to feed her nine year-old son Anthony, who at the beginning of every weekend had to wonder if he would see another meal before the following Monday where he received free school lunches. The government spends less than a dollar per meal on school lunches, which comes to a total of 4.5 billion over ten years – roughly the same amount used in one month of military spending in Afghanistan.

I did feel a sense of grief at the loss of the duck’s life, but that feeling was good in that it grounded me in very real implications of my actions. It also makes me horrified to think of those who have to butcher hundreds of animals in a factory line. How do they feel at the end of the day?

But it doesn’t seem to matter enough. Each day we continue on in the same way – just eating our meat. So when someone asks you if you would like to buy a duck, what will you say?