This spring, my sister and I are boycotting supermarkets. Instead of shopping at big corporate grocery stores, like Walmart, Martin’s and Kroger, we are getting all of our food from the Maple City Market, Mexican stores in Goshen, the Asian Market, the Dented Can and a few dumpsters.

Why are we doing this? Because we believe the current system of producing, selling, consuming and disposing of food is unhealthy, unjust and unsustainable.The large-scale food industry conditions consumers to think we can get whatever food we want any day of the year at an unrealistically low price.

To make this possible, food is grown by underpaid workers using environmentally harmful practices and is transported long distances in fossil fuel-burning vehicles to locations where the produce is not in season. Once at the store, 10% of all food that is shelved never reaches the consumer’s cart and goes to the dumpster instead, according to Quest, a company that works with businesses to reduce their waste.

Because small businesses work on a reduced scale, their owners can be more intentional about sourcing food responsibly, paying employees fairly and making sure food isn’t wasted.

My campaign against mainstream supermarkets may not have a huge impact in and of itself. Walmart, a corporation with more than 2.2 million employees worldwide, made almost $1.5 billion in revenue every day in 2020; because of me and my sister, they will make $30 less this month. But we’re not just seeking a financial impact; we’re conducting this boycott as an expression of our conviction that the system needs to change.

The food system is one of many systems that need to undergo massive changes if we are going to survive climate change, and boycotts are an especially appropriate tool for inciting those changes.

In boycotts, the action serves as an expression of our beliefs, much like words do.

For example, setting fire to an American flag could be a respectful means of disposing of a worn-out flag, but it could also be a dramatic criticism of a government policy.

Actions carried out for their symbolic value are protected by the First Amendment, which makes them a good option for civil activism.

Greta Thunberg, the Swedish climate activist, understands the power of boycotts. When she was 15, she started skipping school every Friday to sit outside the parliament building with a sign reading, “School Strike for Climate.”

Last year, Thunberg took an entire year off from school to travel the world on a zero-carbon sailboat and speak at climate conferences like the UN Climate Action Summit in New York City and the UN Climate Change Conference in Spain. She is back in school this year, but still takes every Friday off to strike.

Thunberg doesn’t skip her classes because doing so will have a direct effect on the climate. She does it to make a statement about her views and to draw attention to climate change.

In her speech at the Summit in New York, Thunberg said, “I shouldn’t be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean.”

That is, under normal circumstances.

Thunberg understands better than most people that a global climate crisis is no time for business as usual, and a school boycott is one way to show that.

“If a few children can get headlines all over the world just by not going to school for a few weeks,” Thunberg said in a Ted Talk in 2018, “imagine what we could all do together if we wanted to.”

Over the past two and a half years, Thunberg has proven that the answer is, quite a lot. The Fridays For Future organization reports over 14 million members around the world who strike for climate action at all levels of government.

School isn’t the only thing worth boycotting for the cause of the climate. Thunberg also boycotts airplane travel and meat.

“We can’t save the world by playing by the rules because the rules have to be changed,” Thunberg said in the Ted Talk. “Everything needs to change and it has to start today.”

I will start by shopping at San Juan Market instead of Walmart. I know I won’t always find the perfect Honeycrisp apples or the exact brand of peanut butter I want, but if all of us learned to not always get what we want, that would be a huge step toward creating a more sustainable future.

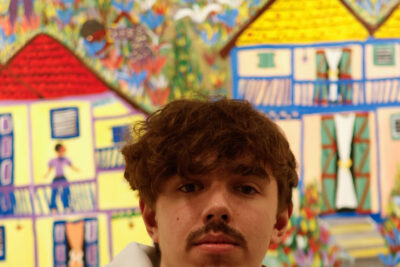

Sierra Ross Richer is a junior journalism major.