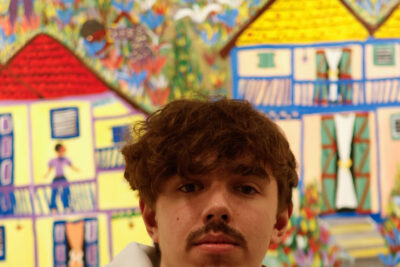

Hayley Brooks is a sophomore English Writing major.

Over the course of the break, I managed to spend nearly all my time meandering through the depths of the Internet. In between Facebooking and finding new feminist blogs, I stumbled onto a blog called “Nice Guys of Ok Cupid.” The blog features the Ok Cupid profiles of self-proclaimed “nice guys” who get put into the “friend zone” because they are just too nice. The moderator of the blog compiles parts of their profiles and their answers to questions that prove that they aren’t so nice after all.What really disturbed me the most in the profiles of these men was the answer to the question: “Which best represents your opinion of same-sex relationships?” The majority of these men either answered “all same-sex relationships are wrong” or “girl-on-girl is ok, but guy-on-guy is wrong.” At first glance, this may look discriminatory only to gay men, but when you dive into the roots of these sort of sentiments, both halves of this statement are misogynistic and hetero-normative. I should also note that throughout this piece, I will refer to the LGBTQ community as the queer community because it is more inclusive. I will also being using cisgender, meaning persons who identify with the gender assigned to them at birth.

The first reason this statement is misogynistic is that much of the reason our society hates and demonizes gay men is because they are typically more feminine than their straight counterparts. Femininity is demonized in our society and is considered to be dependent on maleness and masculinity and is seen as a weakness in all genders. Gay men are not hated for being men; they are hated for being like women and for the obvious reason of being gay in a hetero-normative society.

The second reason this statement is misogynistic is because it objectifies and fetishizes lesbian relationships. The idea that “girl-on-girl” is okay, as deemed by a straight man, is because mass media, the porn industry and the male gaze considers these relationships to be props for their male fantasies. Margaret Atwood once said, “Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy.”

When straight men ask and sometimes demand to know about the intimate details of my life and sexual relationships as a lesbian, or what “parts” of a woman I am attracted to, they are objectifying and fetishizing the way I relate to other human beings and my body. Curiosity and fetishization are different, but there is a fine line between them.

Lesbian relationships, especially relationships between femme lesbians, are considered to exist for the pleasure of cisgender, heterosexual males. It furthers the idea that women exist for men and that women owe men something just for existing. It rests on the idea that men should and can have access to a woman’s body even when she does not want it. Even if you aren’t going to cater directly to a man’s sexual desires as a woman, you better be willing to offer your intimate, romantic relationships because male sexual desires and pleasures should be met before a woman’s. This also rests on the idea that underneath every lesbian is a straight woman who is merely putting on a show for the pleasure and sexual desires of straight men.

These sort of statements are not isolated events, but are embedded into our culture, media and institutions. When heterosexual, cisgender people hold these beliefs to be true, they have the privilege to benefit from them; their self-esteem and self-worth are not damaged. However, when members of the queer community hold onto these beliefs, unconsciously or not, they internalize this hatred. I know what objectification and fetishization does to a person’s sense of self. I have caught myself understanding my body as an object and my worth only in terms of what it can do for men, even though I have never been attracted to men.

In the end, this is a call to understanding the ways in which homophobia, heteronormativity, misogyny and other oppressions are inextricably linked together. It is also a call to understand the ways we continue to perpetuate oppressions in the things we believe in, our language, and in the questions cisgender, heterosexual people continually ask of the queer community.