It seems like we were framed by the cosmos to play a tiny part in history, to experience the tragedies of occupation. In the short story below there were many casualties. Did it have to be that way?

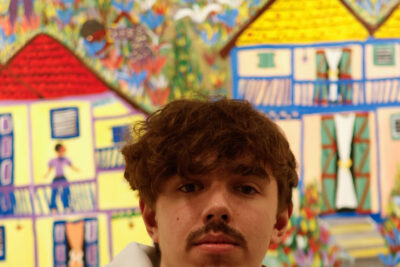

March 25, 1993 was just an ordinary day in my life. I arrived home from work at the usual time. I went into the front room to take off my boots. On the table lay the EVENING PRESS unfolded and already read. My eyes were directed to the large black headlines “THREE DIE IN GUN ATTACK, Loyalist murder gang in massacre at building site,” and a sub heading read “Bomb blast victim dies.” Then drawn to a child’s image I was immediately filled with apprehension. Those eyes. That face. My son. Puzzled, I scrambled through the text for an explanation. I was relieved to read my wife and son Cian had gone to a shrine at St. Stephens Green, where children left teddy bears, cards, and flowers addressed to two boys killed by Irish Republican Army (IRA) bombs in England. I hadn’t expected them to be there at all; my family were longtime supporters of the IRA, but this was a memorial for victims of the IRA. It was like my son was looking at me, saying, “Dad, this is wrong. This little boy’s death could have been mine.”My national aspirations were instilled through story and reinforced through song at a very young age. The verse below, from a very popular nationalist song, was taught in schools throughout the Republic of Ireland. At IRA gatherings, it was a rebel-rousing favorite, guaranteed to raise passion, and recruit young volunteers for the cause.

When boyhood’s fire was in my blood

I read of ancient freemen,

For Greece and Rome who bravely stood,

Three hundred men and three men;

And then I prayed I yet might see

Our fetters rent in twain

And Ireland, long a province, be.

A Nation once again!

My grandmother lived in a small cottage just down the yard from ours. I loved to visit her whenever I could. She would tell stories of the ancient lore of Ireland, of our first ancestors, Na Fir Bolg, who were eventually displaced by successive waves of opportunist invaders, right up to our colonization by the British. Above my grandmother’s mantelpiece proudly hung a rare print of the General Post Office in Dublin, engulfed in flames. It was the major battle ground during the 1916 Easter Rising. I was enthralled by the battle scene in the GPO, and its defense by valiant Irish Volunteers, amidst the dead and dying. In the aftermath of the battle, the leaders were captured and executed at Killmainham Jail. James Connolly the leader of the Dublin Brigade was tied to a chair, and shot dead.

He faced us like a man who knew a greater pain

Than blows or bullets ere the world began: died he in vain

Ready, Present, and him just smiling, Christ I felt my rifle shake

His wounds all open and around his chair a pool of blood

And I swear his lips said, “fire” before my rifle shot that cursed lead

And I, I was picked to kill a man like that, James Connolly

I went to an Irish-speaking Catholic school a couple of miles from the scene of Connolly’s execution and in 1966 I graduated a committed Irish nationalist. Like many youth of my age, I fully supported the sentiment expressed in our national anthem “Amhrán Na bhFiann” (a Soldiers Song) of rallying the people, and kicking British rule out of Ireland, forever.

In the late sixties some of our collective desires and anti-British resentments were to find direction and expression in the civil rights struggle in Northern Ireland. Protest marches to end inequity in housing, employment, and a voting system that kept Catholics powerless, were brutally suppressed by the Protestant Royal Ulster Constabulary. Widespread rioting followed with rising tension and violence between the Protestant and Catholic communities. The Provisionals IRA formed to defend the Catholic nationalists, and to go on the offensive against the brutality of British troops. Many young men in the Republic were incensed by the plight of the Catholic community. They joined the Provisional IRA and underwent armed training. Others, like me, well-oiled by our national rituals, were sympathetic to their aims. A favorite IRA song of mine at the time was the “Broad Black Brimmer.”

It´s just a broad black brimmer with ribbons frayed and torn

By the careless whisk of many a mountain breeze

An old trench coat that´s all battle stained and worn

And breeches almost threadbare at the knees

A Sam Brown belt with a buckle big and strong

A holster that´s been empty many´s a day… but not for long

When men claim Ireland´s freedom the one who’ll choose to lead them

Will wear the broad black brimmer of the IRA

The brutality of the years that followed was horrifying. Many families never saw their siblings or fathers alive again. The UVF, a Protestant paramilitary organization, and the nationalist IRA, were responsible for over sixteen hundred sectarian killings. Decisions made by bigoted, uncompromising politicians who were often inured to the suffering in their midst, and support for the warring factions from outside Northern Ireland, inflamed the violence and prolonged polarization. Despite the genuine efforts of many working for peace and reconciliation, the tragedies continued. One such event occurred in Warrington, England.

March 25, 1993 was no ordinary day for Tim Parry. With permission from his family, doctors took him off life support. He was only twelve years old. Five days earlier, two bombs planted in heavy metal trash cans, exploded in a crowded shopping area in Warrington, England. Johnathan Ball, only three years old, was killed instantly. Tim and 56 other people were seriously injured. The bombs were planted by the Provisional IRA.

Cian’s image in the newspaper that evening, connected in sympathy with Johnathan’s and Tim’s heartbreaking fate from that bomb blast, left me so unsettled and filled with regret. But, why did I continue to have sympathy for aspirations with a deadly shadow side, and why was making peace with the inherited wounds of British occupation impossible. I had slim resources to draw from. Peaceful considerations were never a cultural strong point, nor encoded in my upbringing. At school peace was not a focus, there was no direction in alternatives to violence, and absolutely no instruction regarding the hazards of ritual to independent decision and human life. It is a blessing to speak of peace in safe educational settings and to take the wisdom of that privilege with you. Unfortunately we did not have the wisdom, nor the privilege.

Many of my peers in the ‘60s and ‘70s were passionate and headstrong, possessing a keen sense of injustice, and they wanted to change what was wrong. They were programmed by the history of the place they were born into, and they were inflamed by national rituals and songs.

I have witnessed the brutal effects of national anthems from many personal experiences. I conclude they are highly destructive to human life and they contribute to so much suffering.

*Note: This article was originally published on Jan. 23 on the ‘Stories from National Anthem Conscientious Objectors’ blog, sponsored by faculty, staff, and students at Goshen College who are deeply saddened by the President Council’s decision to make the National Anthem a campus ritual.