You are a cog in a very tight wheel. A blip in overdressed work clothes in a blinding current of flip flops and ethnic beads. The people who sit behind doors half open are at first a mystery, these editors who laugh in the hallway after lunch and know so much more than you, can hope to worry about word counts, punctuation terms, and how to rearrange a sentence so it glows. They carry coffee cups and water bottles into meetings. They speak in terms of paper and cloth and galleys. They always hold pens.

So you begin to try to emulate what they pour out. You pretend as if you know what you are doing when they ask you to look up book sales. You have an entire database at your fingertips that can tell you how many Harry Potter books were sold since the first copy. The numbers shock compared to the books off the presses at Beacon – modest, beautiful books made with so much care but which sometimes fly a bit under the radar. After you read a manuscript in process, a book about immigration set to come out next fall, you think, where are their Harry Potter numbers? The sales pale in comparison but the books themselves – their caliber, their goodness, the sweet singing way each page pushes you along – do not.

On your first day, you meet all the publicists, editors and designers, the mailroom assistant and the custodian and receptionist, and immediately forget their names. Several weeks pass before you meet the director, who is off traveling. Her office seems to have the most air and the most light and she is formal but brilliant. The kind of sharp-witted woman you’ve always wished to be.

In your office there are shelves of books out of print, growing dusty. You alphabetize them all. Towers of manuscripts to be rejected and tossed. The first time you send a rejection letter from a template and seal the envelope, you can not help but remember that you are crushing someone’s dream.

There are days in which you email the author of a book you just finished and tell her travel information for her tour. All your life you have read and never have you been so close to the inside; you could easily reach out and touch the silk bindings before they pour the glue.

The physical books are not made on site but you are in awe of the amount of work needed, the long and heavy marks of each editor shaping the author’s speech. They are all passion. They seem not to tire.

Their line-up this summer is memoirs of same-sex marriage and journeys of transgendered women, revitalized versions of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches. Each one exposes a truth or attempts to make the world see differently, to shape corners. One book is such a heady shade of neon yellow that you are afraid you will blind the other passengers when you read on the train. You hold it up like a torch so all of Boston can see Beacon Press for what it is.

In the late mornings, you leave the press and saunter down cobbled Joy Street, past Robert Frost’s former brownstone, past the ancient residential houses of grandeur to the Public Garden. In the heat of summertime, tourists flock with their cameras and fanny packs. You feel like one of them but you are in heels and carry a paper lunch bag, appearing to them a permanent fixture who knows directions.

When you sit down on a bench overlooking the lagoon, where weeping willows dip their lolling heads toward a duck-pilfered surface, you think of how, no matter the technology, the ability to self-publish, people will always need places like Beacon. No individual alone could put so much intention into seeking out books and shining them up.

There are those who lay down on paper what they want to say and there are those that help them say it. Those people who weed through the muck to find the gems. The ones whose names you now know, whose offices you step into with a legal pad, who notice your new nose piercing and in the end, tell you to come back. You think of Beacon’s words arranged and shipped out and how they are anything but quiet.

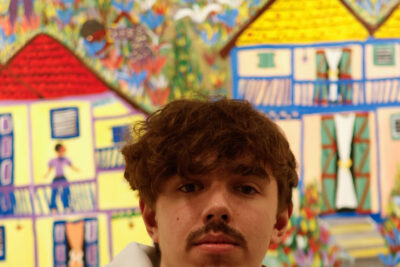

Kate Stoltzfus is a third-year English Writing and Journalism double major.